Do You Suffer From Shoulder Pain?

Staying injury free in the gym is the most important goal you can have. Although the aim is to push the boundaries of your physical potential and to achieve results, an injury may result in weeks or even months of modified training.

Although aches and pains are inevitable for serious bodybuilders and powerlifters, there is plenty you can focus on to help prevent serious injury in your workouts.

This article will focus on the shoulder and the key concepts that can be implemented to maintain healthy shoulders.

Anatomy

The proper functioning of the shoulder, glenohumeral joint (GHJ), is reliant upon five systems:

- A healthy and properly functioning cervical spine (neck)

- A healthy and properly functioning thoracic spine (mid back)

- Adequate strength of the scapular muscles through all lifting patterns

- Adequate strength of the rotator cuff muscles through all ranges of movement

- Adequate strength of the prime movers for that particular exercise & the resistance selected

1. Cervical Spine

Stiffness & dysfunction of the cervical spine can affect the neural output to the muscles surrounding the shoulder complex.

When this occurs the muscles may be unable to properly stabilize & control the scapula or shoulder joint. This may result in faulty movement patterns.

The loading of faulty movement patterns, as would occur in the gym, significantly increases the risk of injury.

Anyone being treated for shoulder pain should have his or her neck cleared for dysfunction.

2. Thoracic Spine

The thoracic spine is made up of 12 segments (T1 to T12). The term used to describe the curve in this part of the spine is kyphosis.

Excessive kyphosis, caused by muscle imbalances and/or poor posture can have a negative impact on the proper functioning of both the cervical spine & the glenohumercal joint (shoulder).

Full range of movement at the shoulder is dependent upon the ability of the thoracic spine to extend or bend backward, to a neutral position. If this cannot be achieved then gym movements such as overhead shoulder pressing pose a serious risk to the joint.

The classic ‘bodybuilder’ rounded shoulder look is an example of excessive thoracic kyphosis. Qualified health professionals can mobilize the thoracic spine to restore posture and movement. Likewise, foam rollers and other posture exercises can be used effectively.

3. Scapular Muscles

These are the main muscles responsible for stabilization of the shoulder blade: Lower, middle & upper trapezius, rhomboids. levator scapulae, & serratus anterior.

Their role is to work synergistically with the muscles of the shoulder joint to ensure correct movement patterns. This is often referred to as ‘scapulo-humeral rhythm’ & is crucial to the proper functioning of the shoulder joint.

Typically, greater emphasis is placed on the rotator cuff complex during rehabilitation or injury prevention. However, without adequate scapular stabilization, the rotator cuff becomes overloaded & susceptible to injury.

The term ‘retraction’ refers to the action of bringing your shoulder blades backward and inwards towards the spine.

4. Rotator Cuff Muscles

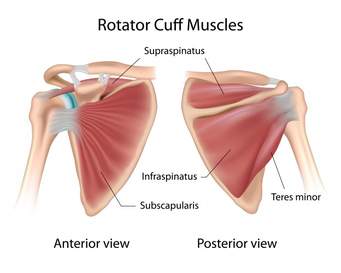

The rotator cuff is made up of four muscles: Infraspinatus, teres minor, supraspinatus, and subscapularis. The main role of the rotator cuff is to assist with stabilization of the shoulder joint. Through their attachment onto the humerus (upper arm bone) the rotator cuff is able to stabilize the humerus within the glenoid cavity (socket) allowing for more efficient movement patterns through the shoulder joint.

The rotator cuff is made up of four muscles: Infraspinatus, teres minor, supraspinatus, and subscapularis. The main role of the rotator cuff is to assist with stabilization of the shoulder joint. Through their attachment onto the humerus (upper arm bone) the rotator cuff is able to stabilize the humerus within the glenoid cavity (socket) allowing for more efficient movement patterns through the shoulder joint.

Dysfunction of the rotator cuff can lead to instability at the shoulder joint and possible injury to any number of structures including tendons, cartilage, bursa or ligaments.

5. Prime Movers

The prime movers are the group of muscles required to perform the desired movement pattern.

Assuming that the other four systems are functioning correctly, then the prime movers are in a position of strength to complete the task at hand -Push, pull, twist, bend, squat, lunge, lift, etc.

Key Concepts

All five systems must be functioning properly to minimize the risk of injury and to maximize performance during any lift.

All five systems must be functioning properly to minimize the risk of injury and to maximize performance during any lift.

Injury often occurs due to failure of one or more of these systems.

Any successful rehabilitation program must include restoration to all five of these systems.

A cortisone injection into a subacrominal bursa or rotator cuff tendon without subsequent rehabilitation of these five systems is unlikely to provide a permanent resolution to the problem.

Following a rotator cuff retraining program without retraining the scapular muscles at the same time is unlikely to have the desired effect.

There are several common misconceptions that are often applied to shoulder function:

‘Training your back (pulling exercises) equally to your chest/shoulders (pushing exercises) will ensure that proper posture is maintained.’

Unfortunately, this statement is false and often leaves weight lifters confused as to why they have poor posture. The prime mover for all pulling exercises is the large latissimus dorsi muscle. Due to their anatomical attachment onto the humerus (upper armbone) these muscles act an internal rotator of the humerus.

What this means is that the tighter these muscles get the more internal rotation occurs and the more rounded the shoulders become (poor posture). As such, repeated back training on its own typically doesn’t improve posture. Specific postural and scapular retraining exercises must be performed weekly for weight lifters to maintain healthy posture.

‘Maintaining retraction of the shoulder blades during all back exercises is ideal.’

Once again this statement is false. The scapula (shoulder blades) are designed to move in rhythm with the shoulders and arms (scapulo-humeral rhythm). This rhythm allows the load to be shared amongst all the muscles. Fixing the scapula in a retracted position while moving the arms in isolation is breaking this natural rhythm. The result is an overloading of the rotator cuff muscles, which can often lead to injury of the rotator cuff.

Weight Lifting

There is no question that intelligent lifting in the gym is paramount to maintaining healthy shoulders.

Technique coaching from an experienced lifter or strength coach can significantly reduce your risk.

Technique coaching from an experienced lifter or strength coach can significantly reduce your risk.

Understanding your body’s limitations in any given set can allow you to complete a set before faulty movement patterns occur. For most lifters, this knowledge and understanding come after many years of weight lifting.

Understanding the difference between muscular fatigue and postural fatigue is crucial. The postural muscle systems are designed to put your joints in a favourable position so that you can perform a given exercise. When the postural muscles fatigue, joint position is lost, and this significantly increases the risk of injury.

Consider this example. You are performing a bent over (bar) row with 100kg. In the initial 6 reps, your scapular muscles are able to retract in rhythm with the movement of your arms (rowing action). From reps 7 onwards your scapular muscles begin to fatigue and you’re no longer able to fully retract the scapula during the rowing action. At this point, your risk of injury to the shoulder joint, cervical spine (neck), thoracic spine (mid back), and acromioclavicular joints (ACJ) increases.

Being aware of postural fatigue should signal you to stop the set at 6 repetitions and minimize your risk of injury.

Trigger Points (Muscle Knots)

If you lift weights long enough you’re guaranteed to develop triggers points. The term ‘trigger point’ was coined by Dr Janet Travell in 1942 and has been used to describe hyper-irritable spots in skeletal muscle that are associated with taut (tight) bands of muscle fibers.

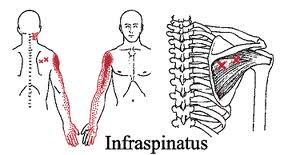

The trigger point can radiate pain to other areas of the body. For example, the rotator cuff muscles can radiate pain to the shoulder joint and upwards towards the neck. The upper trapezius muscles can refer pain into the base of the skull and through the sides of the head towards the eyes.

Shoulder pain is often misdiagnosed as tendonitis (inflammation of a tendon) or bursitis (inflammation of a bursa) when in fact the pain source is one or more ‘active’ trigger points.

Trigger points in the infraspinatus and supraspinatus muscles (rotator cuff) can cause a deep ache in the shoulder.

Treatments aimed at the shoulder joint itself are usually unsuccessful, as they do not address the true source of the pain -trigger points.

For therapists treating powerlifters, bodybuilders, and strongmen, the challenge is threefold:

- Accurate diagnosis of the problem as trigger point related

- Accessing the trigger point (trigger points may lie deep inside the muscle)

- Getting the trigger point to release

The ability to accurately diagnose trigger point stakes years of experience and consistent practice. The client’s description of their pain pattern can alert the treating therapist to the potential muscles involved. Careful palpation (feeling) of the muscle can allow the therapist to identify offending trigger points.

The ability to accurately diagnose trigger point stakes years of experience and consistent practice. The client’s description of their pain pattern can alert the treating therapist to the potential muscles involved. Careful palpation (feeling) of the muscle can allow the therapist to identify offending trigger points.

The second challenge arises if the trigger point lies deep within the muscle (3+cm in depth or greater). The deeper the trigger point lies, the less accessible it becomes to the treating therapist. Often heavy pressure is used to penetrate to the deeper levels.

When the treating therapist is unable to access the trigger points through deep tissue massage, dry needling may become a viable option.

Dry needling is the use of an acupuncture needle to reach the trigger point and subsequently stimulate a ‘twitch response’ or releasing of the trigger point.

Many therapists believe that dry needling not only makes trigger points more accessible but also provides a more thorough releasing effect of the trigger point. The needle has the ability to slide through healthy muscle tissue in order to reach the deeper, underlying trigger point. When the trigger point (knot) releases, both the treating therapist and the client can feel a ‘twitch response’ indicating that the treatment has been successful.

Take Home Message

Spend time each week restoring balance to all five systems that contribute to a Healthy Shoulder. (You may require guidance initially from a qualified therapist to implement a structured program.)

Ensure you have full range of motion in your neck (Cervical spine). If you feel you are restricted in your movements seek the advice of a qualified health professional that can assist you in restoring full range and function.

Mobilize your thoracic spine. This can be accomplished by seeing a qualified therapist, using a foam roller, or through exercises such as Yoga, or with various posture movement patterns.

Stretch Muscles that typically get tight from weight lifting and ‘pull’your body out of position. These include the latissimus dorsi, pectoralis major and minor, rectus abdominis, upper trapezius, scalenii, and sternocleidomastoid muscle groups.

Strengthen the postural muscles that assist with restoring posture and balance to your body. These muscles include your serratus anterior, lower and middle trapezius, rhomboids, thoracic erector spinae, deep cervical flexors, and core muscles. (Strengthen your scapular muscles. Strengthen your rotator cuff muscles.)

Learn to understand the difference between muscular fatigue (of the prime movers) and postural fatigue (of the stabilization systems). End your set when postural fatigue occurs.

Seek consult from a qualified therapist who can assist you with maintaining the health of all five systems. This may include ‘hands-on’ therapy, dry needling, and/or corrective exercises. Consulting a therapist every 2-3 months can help to ensure that you identify muscle and postural imbalances before pain begins.

This article was written by Stephen Hooper: Physiotherapist, Exercise Physiologist, Dry Needling Specialist and director of Effortless Superhuman.

Results may vary.